If you’re wondering why we’re already on Day 7, don’t worry, think of this as something like Star Wars: Episode IV - A New Hope when it came out as the first of the series. If you really must have all the context before moving on and don’t want to wait for the prequels, just go to the Advent of Code 2023 event page and read the backstory there.

I do plan on releasing the prequels for Days 1 through 6, by the way. Just don’t expect them to have any JarJar Bink-sies or any of that kind of silliness.

Advent of Code (AoC) 2023

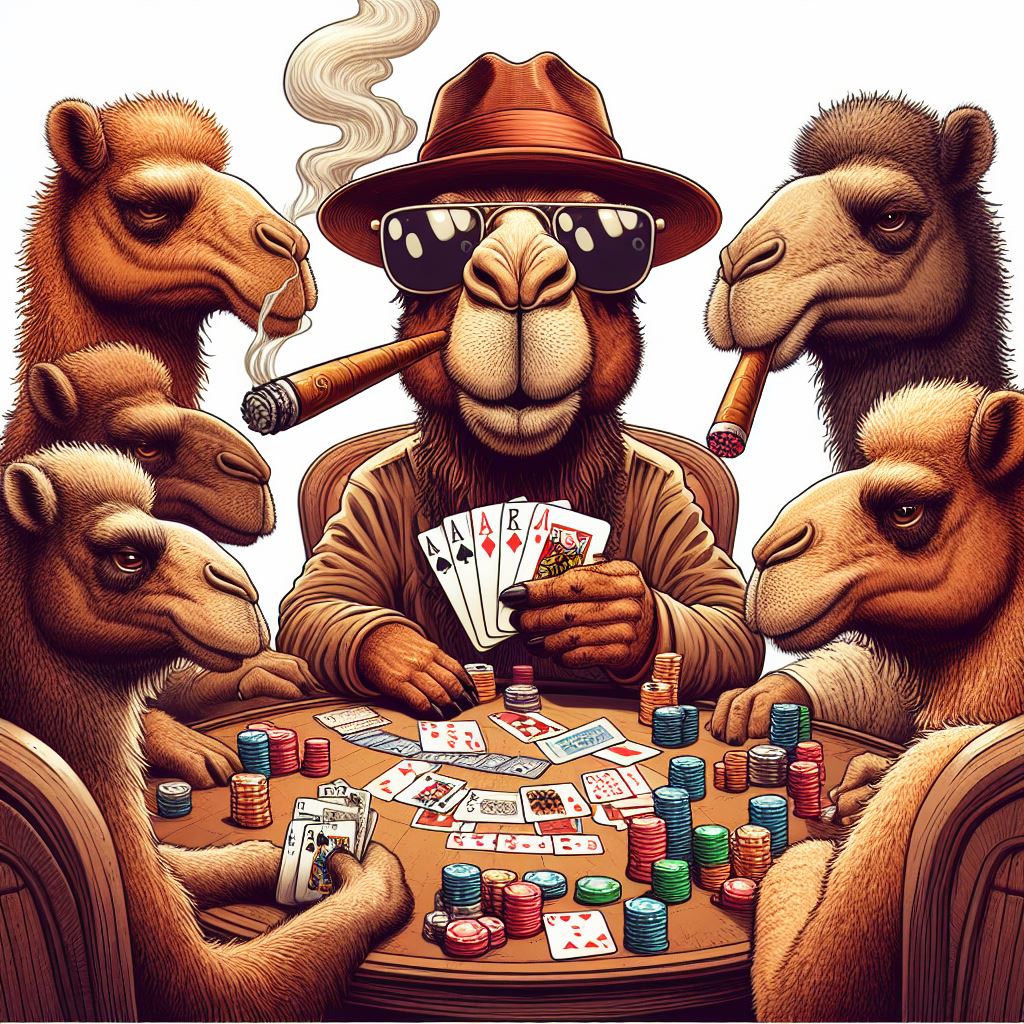

We join our intrepid Kotlin adventurer in the middle of their quest to help fix global snow production. On Day 7, the puzzle is all about Camel Cards, which is like poker, except with a few twists.

First, there are seven types of hands in Camel Cards, the strongest of which is five of a kind where you have, well, five of the same kind of card. For example, the hand TTTTT has five of the Ten (T) kind. Similarly, A7222 is a three of a kind hand because it has three of the 2 kind of card, and 88Q88 is a four of a kind hand because of the four 8 kind cards.

Saying that out loud just now gave me another idea for refactoring.

By the way, if you just want to check out my Kotlin code for AoC 2023, you can find it all here: https://github.com/jlacar/aoc-2023-kotlin/tree/main/src

Caveat: I’m still learning Kotlin. There’s some good Kotlin in there but there’s also quite a bit of not-so-good Kotlin. Feel free to browse, but use at your own risk. You have been warned.

What’s in a name?

I first heard Kent Beck say that “code should tell a story” in a Software Engineering Radio podcast from 2010, Episode 167: The History of JUnit and the Future of Testing with Kent Beck.

Names are the stuff of stories, the fibers of ideas in our programs. We spin them into threads that we then weave into the fabric that we cut and sew together around the problem, to clothe it with what we understand to be the correct solution.

Ok, that was a little deep and dramatic, I admit. But names are an important part of our programs and we would be well-advised to take care and choose them wisely, or run the risk of detracting or distracting from the story the code is trying to tell.

When I highlighted “five of a kind” a few paragraphs ago, and explained the “of a kind” hand type, it occurred to me that rather than using rank, I should use kind instead in that part of my Day 7 solution.

That is, I should refactor-rename this:

fun of(hand: String): HandType {

val distinctRanks = hand.charCounts()

return when (distinctRanks.count { it.value > 0 }) {

1 -> FIVE_OF_A_KIND

2 -> if (distinctRanks.any { it.value == 4 }) FOUR_OF_A_KIND else FULL_HOUSE

3 -> if (distinctRanks.any { it.value == 3 }) THREE_OF_A_KIND else TWO_PAIRS

4 -> ONE_PAIR

else -> HIGH_CARD

}

}

to this:

fun of(hand: String): HandType {

val distinctKinds = hand.charCounts()

return when (distinctKinds.count { it.value > 0 }) {

1 -> FIVE_OF_A_KIND

2 -> if (distinctKinds.any { it.value == 4 }) FOUR_OF_A_KIND else FULL_HOUSE

3 -> if (distinctKinds.any { it.value == 3 }) THREE_OF_A_KIND else TWO_PAIRS

4 -> ONE_PAIR

else -> HIGH_CARD

}

}

I think the name “kinds” fits better in this part of the code, especially since the enum type HandType uses “OF_A_KIND”. I realize now that “rank” is problematic because it’s also used elsewhere, but with a different meaning and an entirely different idea from the one we’re dealing with here in the HandType.of() function.

With distinctKinds, the idea in the code now matches the idea in my head. Gone is that subtle little bit of dissonance between “rank” and “kind”. “Rank” was, as they say, a loose thread that we have just tied off. The code is now more consistent and coherent.

That’s what’s in a name.

Use names from the problem domain

Speaking of names, a rich source of good ones for our programs is the problem domain itself. You can tap into what Eric Evans and the Domain Driven Design folks call “the Ubiquitous Language”, a set of words and terms used to give context and meaning to ideas related to the problem at hand.

Engineers, being technical by nature, love to use technical-sounding names. That’s just what we do. However, techie-speak often creates problems in communication, especially when it comes to non-engineers.

Translations between techie-speak and nontechie-speak must constantly happen when these two groups try to communicate with each other. Having a common ubiquitous language reduces the noise in the system and helps keep everyone on the same page.

Here are other examples from my Day 7 solution that use language from the puzzle description:

enum class HandType {

HIGH_CARD, ONE_PAIR, TWO_PAIRS, THREE_OF_A_KIND, FULL_HOUSE, FOUR_OF_A_KIND, FIVE_OF_A_KIND;

val strength: Char = 'A' + this.ordinal

// ...

}

override fun part1(): Int = totalWinnings(plays.sortedWith( compareBy { it.normalStrength } ))

override fun part2(): Int = totalWinnings(plays.sortedWith( compareBy { it.jokerStrength } ))

private fun totalWinnings(rankedPlays: List<CamelCardPlay>): Int =

rankedPlays.mapIndexed { rank, play -> (rank + 1) * play.bid }.sum()

You’ll notice the use of “rank” in the totalWinnings() function that I previously alluded to. Here, “rank” denotes a hand’s relative order based on its strength, as compared to the strength of other cards. This, by the way, is what the part1() and part2() functions are talking about. AoC wants us to “Find the rank of every hand in your set” and answer the question “What are the total winnings?”

See how the ubiquitous language works?

Extension functions and type aliases help to add fluency

I love fluent APIs, which also tap into the power of the ubiquitous language. Here’s some code in the Day 7 solution that uses the StrengthMapping type alias and a String.charCounts() extension function to add a touch of fluency to the Kotlin code:

// in Day07.kt

typealias StrengthMapping = Map<Char, Char>

...

private val countOf = hand.charCounts()

private val jokerHand = if ((countOf['J'] ?: 0) == 0) hand else hand.replace('J', mostNotJ())

private fun mostNotJ() = countOf.filterNot { it.key == 'J' }.maxByOrNull { it.value }?.key ?: 'A'

val normalStrength = strength(HandType.of(hand), hand, normalRules)

val jokerStrength = strength(HandType.of(jokerHand), hand, jokerRules)

...

fun strength(handType: HandType, hand: String, strengthOf: StrengthMapping) =

hand.fold(handType.strength.toString()) { strengthSoFar, nextCard ->

strengthSoFar + strengthOf[nextCard]

}

// in Utils.kt

fun String.charCounts(): Map<Char, Int> = mutableMapOf<Char, Int>()

.let { countOf ->

forEach { ch -> countOf[ch] = countOf.getOrDefault(ch, 0) + 1 }

countOf

}

The difference between charCounts(hand) and hand.charCounts() may seem trivial but in my opinion, the latter reads much better. I like to read code out loud so I can literally hear what it’s saying. Maybe it’s just me but something in my brain seems to click more cleanly when I hear myself say “count of cards in this hand” as I read hand.cardCounts() versus when I read cardCounts(hand).

Wait, did you notice what just happened? I just heard myself say “card counts” but my eyes are reading “charCounts()”. In fact, I just wrote cardCounts() instead of charCounts().

We’ve just found some dissonance in the code! I was thinking “card counts” but the code was saying “char counts”. Good thing I was trying to explain it to you. No problem, we can always alias charCounts() with an extension function.

// local String extension for story consistency

private fun String.cardCounts(): Map<Char, Int> = this.charCounts()

private val countOf = hand.cardCounts()

Ironically, charCounts() is already an extension function, one that I created to clarify what a forEach {} operation was doing. Now we’re using an extension function to align the name charCounts() to the problem domain language by referring to it as cardCounts().

Remember what I said before about techie-speak and words in the problem domain? “Char” is techie-speak, whereas “Card” is not; it comes from the problem domain.

Pretty cool, right? Now the Kotlin code also says “card counts” just like how I was reading it out loud: hand.cardCounts().

This is what I refer to as “listening to what the code wants to say.” That is fluency, and getting it requires some sensitivity and paying attention.

How to read code out loud

I probably should say something about this idea of reading code out loud. By that I don’t mean reading it out literally, as in “private val count of equals hand dot card counts.” No, that would be kind of silly.

When I read the code out loud, I try to be “the voice” of the code. I imagine the code as its own person, someone who’s trying to explain an idea to others.

When I read code like private val countOf = hand.cardCounts() out loud, I’ll typically express it as something like “the variable countOf gets assigned the count of each kind of card in the hand.” I imagine that’s really what “the code” is saying. In reality, it’s what I understand the code is saying.

Of course, the exact phrasing also depends on who’s listening. If I’m reading out loud to programmers, I might color it a little technical: “Create an immutable variable countOf for the count of each kind of card in the hand.” Or leave out the “immutable variable” part if I know they already understand what val countOf is saying.

If I’m reading out loud to non-techies, I’ll probably say “We count how many of each kind of card there are in this hand.”

The point is, rather than a literal reading of the code, I think about what the code means and verbalize my understanding. This verbalization is adjusted according to how I think it will be best received by whoever is listening at the moment.

Listening to myself speaking for the code just now helped me find yet another opportunity to refactor. This happens to me quite often. I think it has to do with using two different channels of sensory input: the visual alongside the aural. When I hear something that doesn’t quite match what I’m seeing, it tells me there might be something off in the code.

Getting on the same page

Martin Fowler is often quoted as saying “Any fool can write code that a computer can understand. Good programmers write code that humans can understand.”

This idea is key to writing readable code. You have to consider your audience, which we musn’t always assume will be tuned in to techie-speak. When we do mob programming, or “ensemble” or “software teaming” if that’s what you like to call it, it’s not always just programmers we’re working with. Enabling non-programmers to read the code and understand the ideas in it helps get and keep everyone on the same page.

Conclusion

I hope you’ve learned something from this. I sure as heck learned a few things as I worked through the Day 7 puzzle this year. Certainly, I discovered more about Kotlin that again delighted my inner programmer and pulled me deeper into fanboi-dom. But I also gained deeper insights into things I’ve been coaching others to do over the years, like “read the code out loud,” and “choose good names that help tell the story.”

I plan on getting back in the saddle and start working on my blog again. There’s more to come on AoC Day 7 and cool Kotlin features I’ve discovered and used. Hope you come back soon.

And if you celebrate it, Merry Christmas! Otherwise, have a blessed holiday.

Or as old St. Nick might say, Happy coding to all, and to all a good night!